Featured

-

Bird flu spreads to cows, infects dairy herds in 8 states

This month, federal authorities have been investigating an outbreak of the bird flu in dairy farms. While this virus primarily infects avian species, it has started to spread to other…

-

Bus rapid transit University Line will connect Oakland, Downtown

Pittsburgh’s bus rapid transit (BRT) University Line project continues, with transit-only travel lanes and street…

-

Pennsylvania primary election: Summer Lee wins democratic nomination

On April 23, Pennsylvania held its primary elections to determine who will be on the…

-

Falling in love with ‘The Fall Guy’

Last week, I had the wonderful opportunity to see an early showing of “The Fall Guy” in McConomy Auditorium ahead…

-

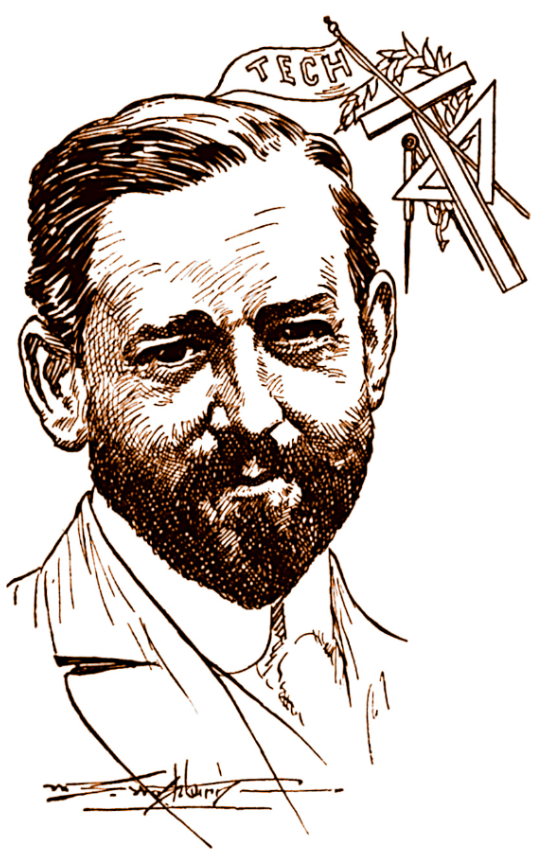

Some history on the guy who built CMU

Henry Hornbostel is an architect with his stamp all over Pittsburgh. His designs grace our skyline in buildings like the…

-

‘Challengers’ review

SPOILER WARNING: I spoil the movie (no more than the trailer already does). When I first saw the trailer for…

-

Bus rapid transit University Line will connect Oakland, Downtown

Pittsburgh’s bus rapid transit (BRT) University Line project continues, with transit-only travel lanes and street improvements planned between Oakland and…

-

Pennsylvania primary election: Summer Lee wins democratic nomination

On April 23, Pennsylvania held its primary elections to determine who will be on the ballot in the November general…

-

State rep. Dan Frankel discusses recent house bills

On March 27, House Bill 777, a regulation of “ghost guns,” passed in the Pennsylvania…

-

Cease the CMU cynicism!

The Beach Boys’ 1963 anthem of educational patriotism, “Be True to Your School,” opens with…

-

Pennsylvania primary election: Summer Lee wins democratic nomination

On April 23, Pennsylvania held its primary elections to determine who will be on the…

-

State rep. Dan Frankel discusses recent house bills

On March 27, House Bill 777, a regulation of “ghost guns,” passed in the Pennsylvania…

-

The Originals perform farewell show after 27 years of a capella

Since 1996, the men’s acapella group The Originals has wowed Carnegie Mellon with their sweet…

-

Highmark Center to open in August, expand CMU wellness

In 1924, the original Skibo Gymnasium opened on the Tech Street hill. Carnegie Mellon’s first…

-

Senate, GSA hold annual Joint Ratification Meeting, elect DoO

On Wednesday, April 17, the Undergraduate Student Senate and the Graduate Student Assembly (GSA) met…

-

CUC waste audit finds majority of food trash could be diverted

A recent audit of waste generated on the second floor of the CUC found that…

-

Dave and Andy’s serves final scoop

By Lora Kallenberg and Haley Williams On Sunday, April 21 Dave and Andy’s Homemade Ice Cream announced that it would be closing. “After 40 amazing years of serving Pittsburgh our…

-

Bus rapid transit University Line will connect Oakland, Downtown

Pittsburgh’s bus rapid transit (BRT) University Line project continues, with transit-only travel lanes and street improvements planned between Oakland and Downtown, involving the 61A, 61B, 61D, 71B, and P3 lines.…

-

Biden tours PA ahead of Tuesday primary

On April 17, President Joe Biden visited the United Steelworkers (USW) headquarters during the Pittsburgh…

-

Students, Prof. Cullen discuss free, civil dialogue

On Tuesday, April 9, Carnegie Mellon SPEAK (Students Practicing Effective Argumentation and Knowledge) hosted an…

-

Students, faculty discuss what AI has become

On April 5, Carnegie Mellon students and faculty gathered in a Doherty lecture hall to…

-

Video game-themed booths line midway, SDC wins best overall

Every year in the week leading up to Carnival, many organizations on campus call all…

-

Thousands gather outdoors to witness rare solar eclipse

By Sam Bates and Arden Ryan Just after 2 p.m. on April 8, the Pittsburgh…

-

A voter’s guide to the upcoming PA primary election

On April 23, Pennsylvania will hold its primary elections. The winners of these races will…

-

The quirks of studying at a university in transition

Editorials featured in the Forum section are solely the opinions of their individual authors. Growing…

-

EdBoard: the eyes of the nation are on college campuses. How should we respond?

Early in the morning on Wednesday, April 17, Columbia students formed the “Gaza solidarity encampment”…

-

The sad, slow, decline of corporate research labs

Editorials featured in the Forum section are solely the opinions of their individual authors. I…

-

Novel-Tea: The wisdom of YA writing

Editorials featured in the Forum section are solely the opinions of their individual authors. I…

-

CMU professor’s research on vaccination behavior

By Abigail Bao On Friday, April 26, Gretchen Chapman, the department head and professor of…

-

Bird flu spreads to cows, infects dairy herds in 8 states

This month, federal authorities have been investigating an outbreak of the bird flu in dairy…

-

An ode to von Neumann, one of the greatest mathematicians

There’s a joke among mathematicians — though I’d caution you that mathematicians are not very…

-

Strange science: Why gum makes water taste so cold

I am the type of person who loves to snack, especially when I study. Chewing…

-

Women’s soccer spotlight: Caitlynn Owens

Caitlynn Owens, a first-year master’s student in biomedical engineering, excels in soccer at Carnegie Mellon.…

-

High seas: Freezing the waves

Baseball and hockey both suck this week

-

Pens Missed The Playoffs – A Brief Summary of the Teams That Didn’t (Eastern Conference)

A brief overview of Eastern Conference teams that made it to the NHL postseason

-

Case Watch

CASE SUCKS

-

‘EMOTE’: An original musical

Walking past the bulletin boards around campus last week, a poster caught my eye. It…

-

Falling in love with ‘The Fall Guy’

Last week, I had the wonderful opportunity to see an early showing of “The Fall…

-

Some history on the guy who built CMU

Henry Hornbostel is an architect with his stamp all over Pittsburgh. His designs grace our…

-

‘Challengers’ review

SPOILER WARNING: I spoil the movie (no more than the trailer already does). When I…