Featured

-

Cease the CMU cynicism!

The Beach Boys’ 1963 anthem of educational patriotism, “Be True to Your School,” opens with the following lyrics: “When some loud braggart tries to put me down And says his…

-

CUC waste audit finds majority of food trash could be diverted

A recent audit of waste generated on the second floor of the CUC found that…

-

Biden tours PA ahead of Tuesday primary

On April 17, President Joe Biden visited the United Steelworkers (USW) headquarters during the Pittsburgh…

-

Biden tours PA ahead of Tuesday primary

On April 17, President Joe Biden visited the United Steelworkers (USW) headquarters during the Pittsburgh leg of a statewide campaign…

-

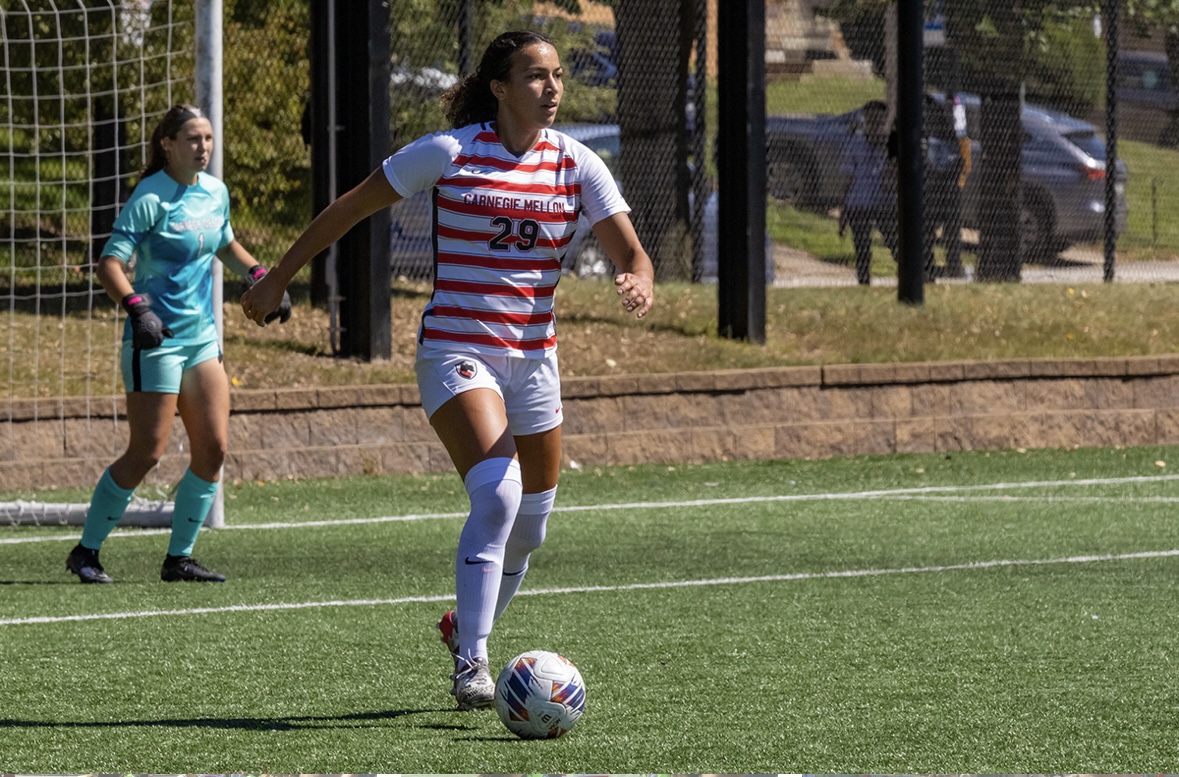

Women’s soccer spotlight: Caitlynn Owens

Caitlynn Owens, a first-year master’s student in biomedical engineering, excels in soccer at Carnegie Mellon. Her academic focus aligns with…

-

Softball takes three wins, one loss over NYU in double double header

The Carnegie Mellon softball team had mixed results in their recent games, with a win against New York University but…

-

‘The Tortured Poets Department’ and Taylor Swift’s right to her own art

Taylor Swift’s April 19 album “The Tortured Poets Department” was announced at the Grammys earlier this year and released on…

-

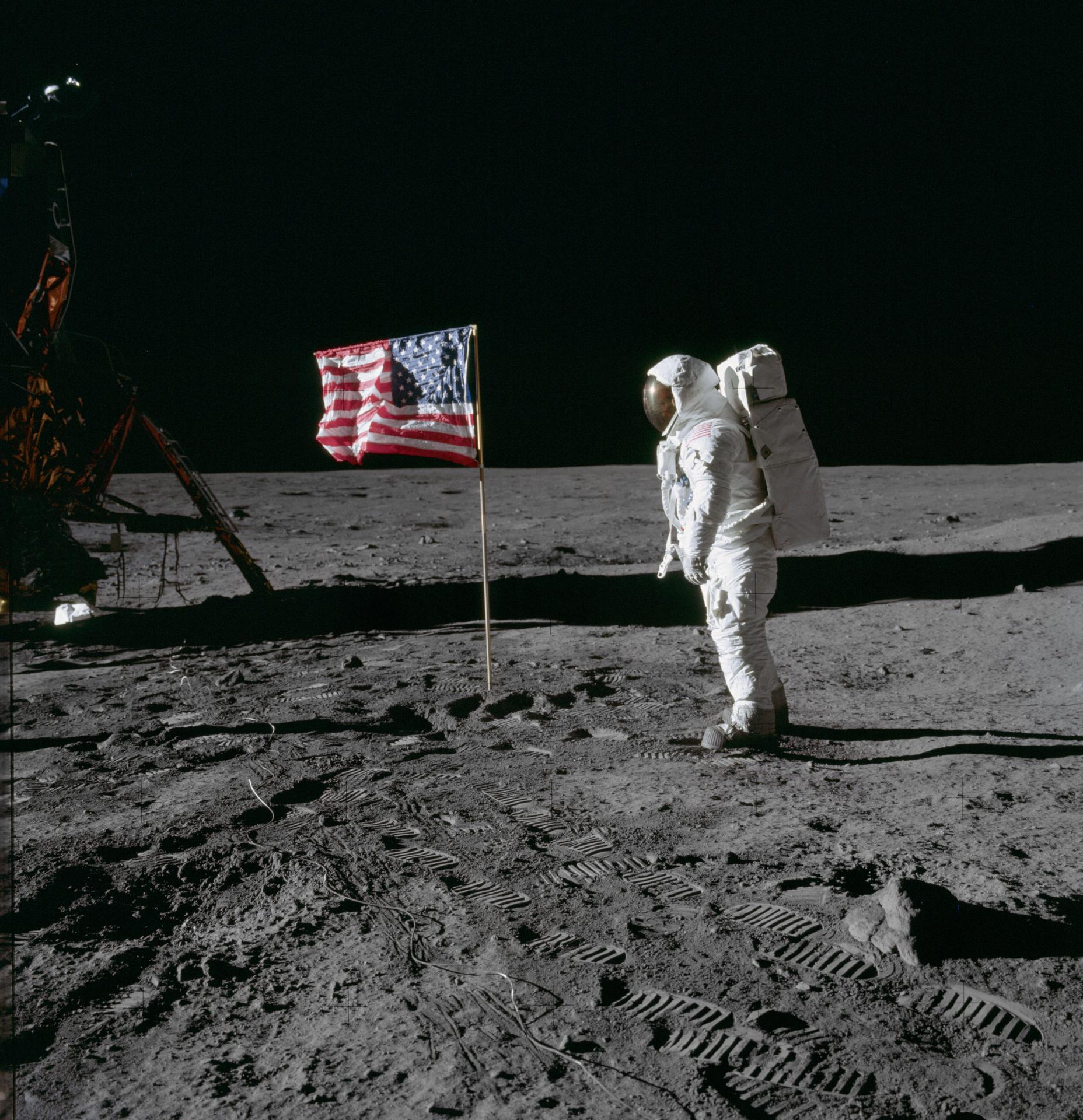

White House directs NASA to create moon time

On April 2, the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy released a memo…

-

Strange science: The accent-changing syndrome

When Sarah Colwill spoke, it was always with a Devon drawl, with all its softened…

-

Meeting (and subverting) college expectations

Editorials featured in the Forum section are solely the opinions of their individual authors. When…

-

Biden tours PA ahead of Tuesday primary

On April 17, President Joe Biden visited the United Steelworkers (USW) headquarters during the Pittsburgh…

-

Students, Prof. Cullen discuss free, civil dialogue

On Tuesday, April 9, Carnegie Mellon SPEAK (Students Practicing Effective Argumentation and Knowledge) hosted an…

-

Students, faculty discuss what AI has become

On April 5, Carnegie Mellon students and faculty gathered in a Doherty lecture hall to…

-

Video game-themed booths line midway, SDC wins best overall

Every year in the week leading up to Carnival, many organizations on campus call all…

-

Thousands gather outdoors to witness rare solar eclipse

By Sam Bates and Arden Ryan Just after 2 p.m. on April 8, the Pittsburgh…

-

A voter’s guide to the upcoming PA primary election

On April 23, Pennsylvania will hold its primary elections. The winners of these races will…

-

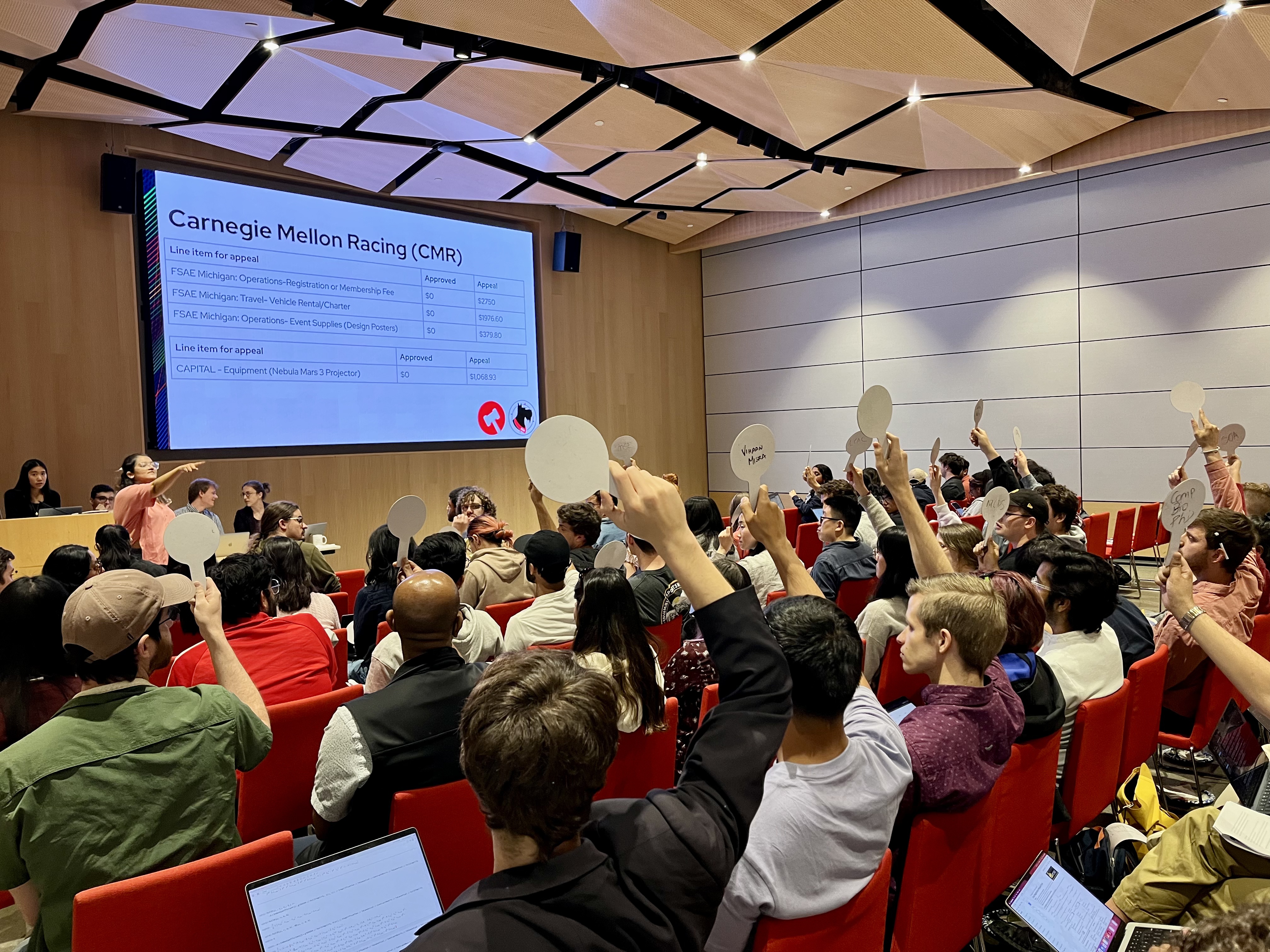

Senate, GSA hold annual Joint Ratification Meeting, elect DoO

On Wednesday, April 17, the Undergraduate Student Senate and the Graduate Student Assembly (GSA) met in Tepper Simmons Auditorium for their annual Joint Ratification Meeting (JRM). In previous years, the…

-

CUC waste audit finds majority of food trash could be diverted

A recent audit of waste generated on the second floor of the CUC found that 83.6 percent of the material tossed into landfill bags could have been recycled, composted, or…

-

CMU holds Spring farmers market

On Tuesday, April 9, the Spring Farmers Market returned to Carnegie Mellon. Vendors at the…

-

Students enjoy Carnival despite rainy weather

By Nina McCambridge Last week, tents and rides began going up on the Cut as…

-

UG2 execs visit campus after custodians publicize contract violations

A week after The Tartan published custodians’ testimonies about contract violations, three senior executives from…

-

Former US ambassador to Myanmar Mitchell discusses spreading democracy abroad

On Thursday, April 4, Carnegie Mellon’s chapter of the Alexander Hamilton Society hosted a talk…

-

Modern Languages department renamed

On March 25, Carnegie Mellon announced that it would be renaming the Department of Modern…

-

Low student turnout in recent Senate elections

Last week, about five percent of students voted in the student government elections. While only…

-

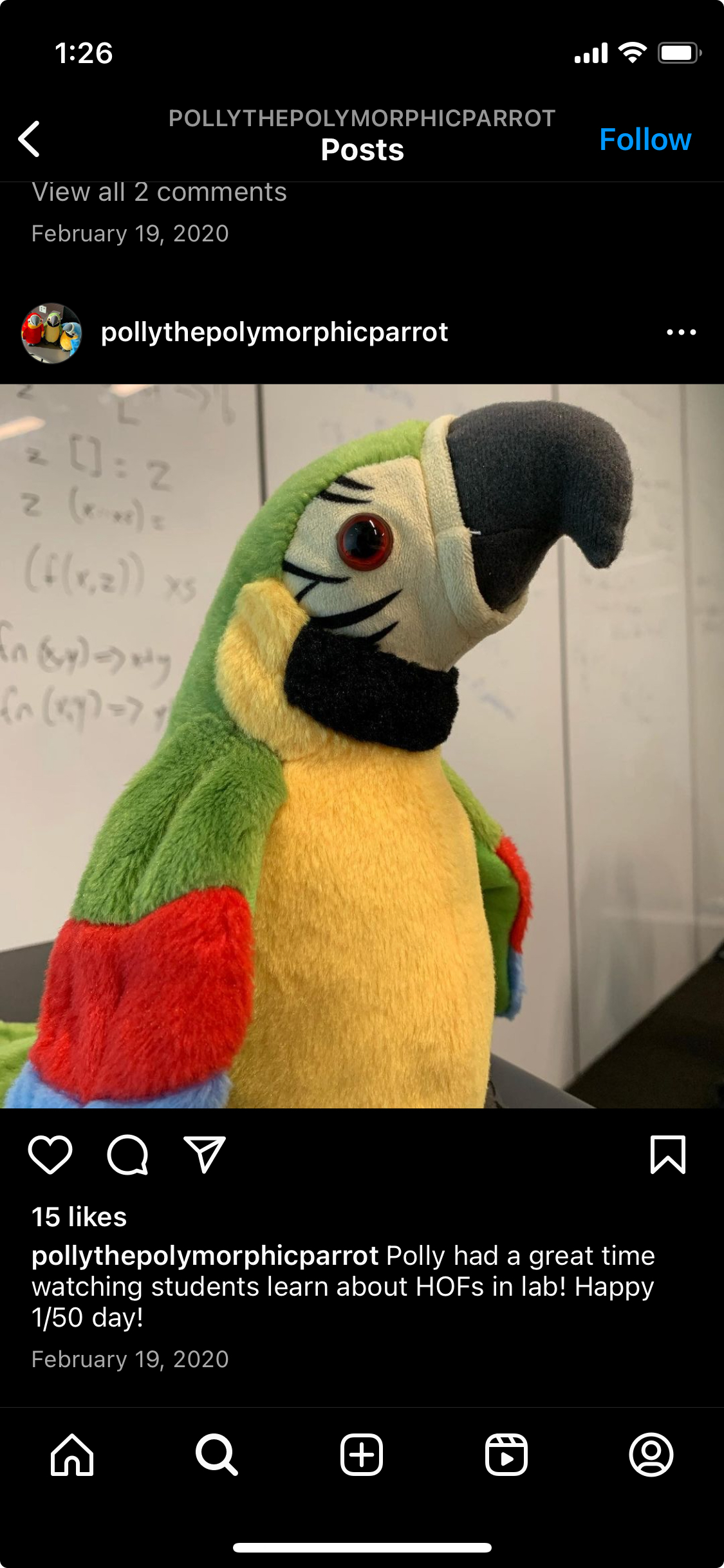

You should be a teaching assistant

Being a teaching assistant is good, and it’s something you should do. With such a…

-

Novel-tea: Remember to think like a child

I think we all need to tell people stories. I talk a lot about stories…

-

PA primaries and a DA discussion

Did you register to vote? Probably not; voting is for old people. Besides, who cares…

-

A take on teaching assistant taxonomy

I have a lot of respect for my TAs, even the bad ones. It’s not…

-

Humane’s Ai pin heavily criticized following its release

The company formerly known as hu.ma.ne — now Humane — has begun shipping its flagship…

-

White House directs NASA to create moon time

On April 2, the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy released a memo…

-

East coast shaken up! What’s behind this earthquake?

On April 5, a 4.8 magnitude earthquake struck New Jersey, more specifically the city of…

-

Strange science: The accent-changing syndrome

When Sarah Colwill spoke, it was always with a Devon drawl, with all its softened…

-

Women’s soccer spotlight: Caitlynn Owens

Caitlynn Owens, a first-year master’s student in biomedical engineering, excels in soccer at Carnegie Mellon.…

-

High seas: Freezing the waves

Baseball and hockey both suck this week

-

Pens Missed The Playoffs – A Brief Summary of the Teams That Didn’t (Eastern Conference)

A brief overview of Eastern Conference teams that made it to the NHL postseason

-

Case Watch

CASE SUCKS

-

‘The Tortured Poets Department’ and Taylor Swift’s right to her own art

Taylor Swift’s April 19 album “The Tortured Poets Department” was announced at the Grammys earlier…

-

Maggie Rogers’ ‘Don’t Forget Me’ is euphoric

It’s a double album review kind of week, because I’ve had Maggie Rogers’ third record,…

-

A Ramblin Wreck

By Eshaan Joshi

-

Carnival 2024

By Kate Myers